— 10 min read

6 Types of Construction Projects: Key Differences for Owners & Contractors

Last Updated Nov 29, 2023

Last Updated Nov 29, 2023

Construction projects are often categorized based on their scale, the types of structures being built, and the purpose of the project (also called "end use" or "land use"). Broadly, there are six types of construction projects: residential, commercial, institutional, mixed-use, industrial and heavy civil.

Urban planners often categorize projects based on their "end use" to ensure development projects meet the varying needs of the communities in which they are built. Describing construction project types by their use can also help project owners and contractors understand the legal requirements – like compliance with zoning ordinances and building codes – and anticipate the engineering needs and environmental impacts of the project.

Because of the vast differences in scope, scale, cost, engineering requirements, equipment and building material needs, developers and contractors frequently specialize in a particular type of construction project (or several closely related types). Some contractors may also structure their organizational chart to include different business units, with each focused on a different type of construction.

Table of contents

1. Residential projects

Residential construction describes structures built for habitation. This category can be broken down further into single-family and multi-family construction. But even then, "multi-family" is often too broad a category to adequately describe a project's needs and considerations.

Consider the construction of a duplex versus a condominium complex. While both are technically multi-family units, there is a significant difference in scale, cost, building materials and engineering needs. From the perspective of both owners and contractors, construction of a high-density residential project (like a high-rise apartment building) generally has more in common with a commercial project than other types of residential projects.

2. Commercial projects

Commercial construction is a broad category that can describe a wide variety of business facilities. These include offices, retail stores, shopping centres, hotels and other facilities built for commercial use.

Compared to residential construction, commercial projects are exponentially more complex. Commercial developers and designers must consider a vast array of needs – including function, safety, environment, energy efficiency and accessibility, to name a few.

Watch a 2-minute video explaining some common differences between project types.

Typically, the price tags on these projects often require contractors and subcontractors to meet stricter standards for prequalification than residential contractors, like the bonding capacity to support the contract amounts.

The gap between residential and commercial construction is widened by the sharp increase in financial risk, especially in the predevelopment phase. Project owners will almost certainly need approval from a governing body or council in order to proceed – without approval, they are unlikely to qualify for the financing they need to fund the project.

Commercial construction projects must comply with specific building codes and standards that address public safety (like fire resistant materials, fire protection systems, emergency exits) and energy efficiency. Commercial buildings are also generally required to include accessibility features that comply with the Accessible Canada Act (ACA).

3. Mixed-use projects

Mixed-use construction projects combine multiple types of construction and land use within a single development or area. Mixed-use developments are designed to create more efficient and integrated communities by providing a variety of functions in close proximity to each other. They often include a mix of residential and commercial units, recreational facilities, green space and public amenities to create vibrant, convenient urban or suburban environments.

Mixed-use developments are popular among developers as a tool to reduce financial risk, allowing them to diversify their portfolio within the same building. If demand for office space weakens (say, during a pandemic), the residential and retail units may help the owner mitigate their losses. However, accommodating multiple end uses within a single development invites an increase in project complexity at almost all phases of the project – and a corresponding rise in operational risk.

While there is a virtually endless variety of configurations, there are four common types of mixed-use construction projects: vertical mixed-use, horizontal mixed-use, transit-oriented developments and live-work-play communities.

Vertical mixed-use

A vertical mixed-use project stacks different end uses within a single building – for example, retail spaces on the ground floor, office spaces on middle floors, and residential units on upper floors. They are common in densely populated areas, especially as urban infill, where property is scarce.

Horizontal mixed-use

Where vertical mixed-use projects build up, horizontal mixed-use developments build out. As a result, this type of project is more common in suburban settings where space is cheaper and more readily available. Individual buildings within the development typically have their own designated uses.

Transit-oriented developments

Transit-oriented developments (TODs) include a variety of facilities (residential units, office space, retail stores, public amenities) designed within walking distance of public transit hubs (e.g. train stations or bus terminals), to reduce reliance on private vehicles. These projects often combine vertical and horizontal mixed-use developments.

TODs may coincide with the launch of a new transit station, or may be built to revitalize adoption of an existing but underused hub. Developers can often qualify for federal or provincial funds earmarked to encourage investment in transit-oriented developments, which foster increased ridership and improvements in community connectivity and accessibility.

Live-work-play communities

Live-work-play communities are designed to include a variety of options for living, working and pursuing leisure or recreational activities within the same neighborhood. Often built as horizontal developments spanning multiple blocks or even hectares, live-work-play communities are increasingly common in suburban locations.

4. Institutional projects

Institutional construction generally describes projects intended for public use, such as educational institutions, hospitals, government buildings and other public service facilities. In a way, this type of project is a "public" version of a commercial project.

While many institutional projects are public projects (i.e. owned by a public agency), they may also be privately developed, owned and/or operated. As a result, there is significant overlap between commercial and institutional construction when it comes to design requirements, building materials and equipment needs.

5. Industrial projects

Industrial construction describes projects built for industrial use, such as manufacturing plants, warehouses and power plants. Examples include factories, chemical processing facilities and oil refineries.

Industrial projects are often subject to heavier governmental regulation, especially with respect to environmental impact. These types of projects typically require a high degree of specialized engineering, with material specifications not often found in other construction projects.

6. Heavy civil projects

Heavy civil construction describes large-scale engineering projects typically associated with infrastructure or public works. These projects include transportation systems (e.g. highways, bridges and tunnels, railways, airports), utilities (e.g. water and sewage systems, communication and power distribution networks) and other large-scale public works projects.

Civil and infrastructure projects are typically highly engineered with complex designs. As a result, the predevelopment and preconstruction phases can be incredibly extensive. It is not uncommon for preconstruction on a civil project to span multiple years.

The pool of contractors available to agencies undertaking civil or infrastructure projects tend to be significantly more limited than on other types of projects. This is in large part due to the high barriers to entry: Heavy civil projects often require specialized heavy equipment and demonstrated experience delivering unique project specifications.

Contractors often start out subcontracting on smaller civil projects in order to build their resume – and relationships – before tendering on bigger government contracts.

Regulatory & safety factors affecting project types

Categorizing a construction project by the end use can give owners, engineers, and contractors valuable information about the project's scale, material and equipment needs, and contractor qualifications required to deliver it. However, provincial and local governments categorize projects in a few different ways – often based on building codes and other safety requirements – that can affect the project specifications, cost and timeline.

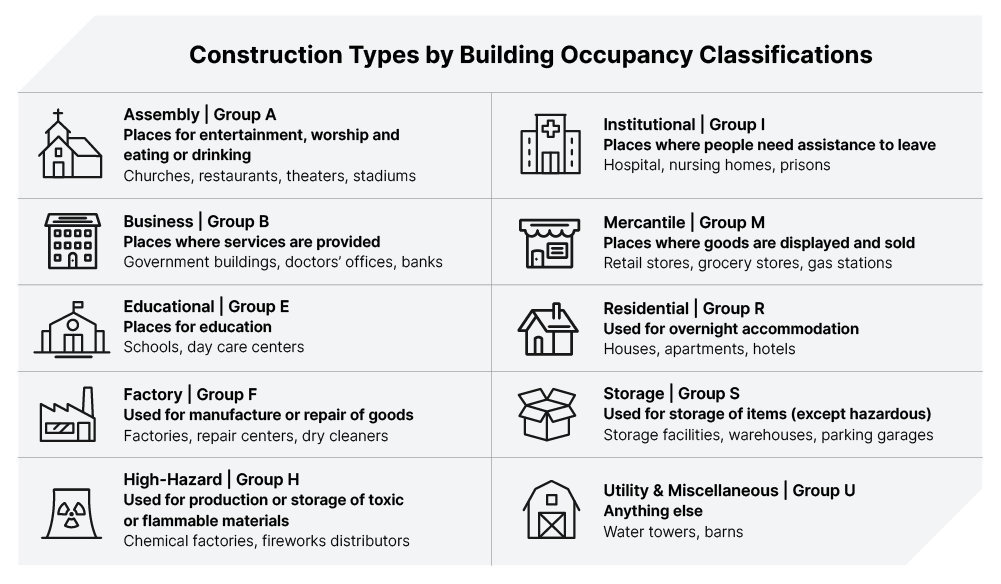

Building occupancy

Local governments classify buildings by occupancy, which refers both to their use and the number of people allowed to occupy the facility. The type of occupancy is important for project owners, architects, engineers and contractors, as they can affect both zoning and building codes.

Because the occupancy classification can determine the design specifications that a construction project must meet, they are important for all project stakeholders to understand and follow closely.

Non-compliance at any point of a project, from predevelopment through project close out, can cause unnecessary schedule delays and lead to budget overruns.

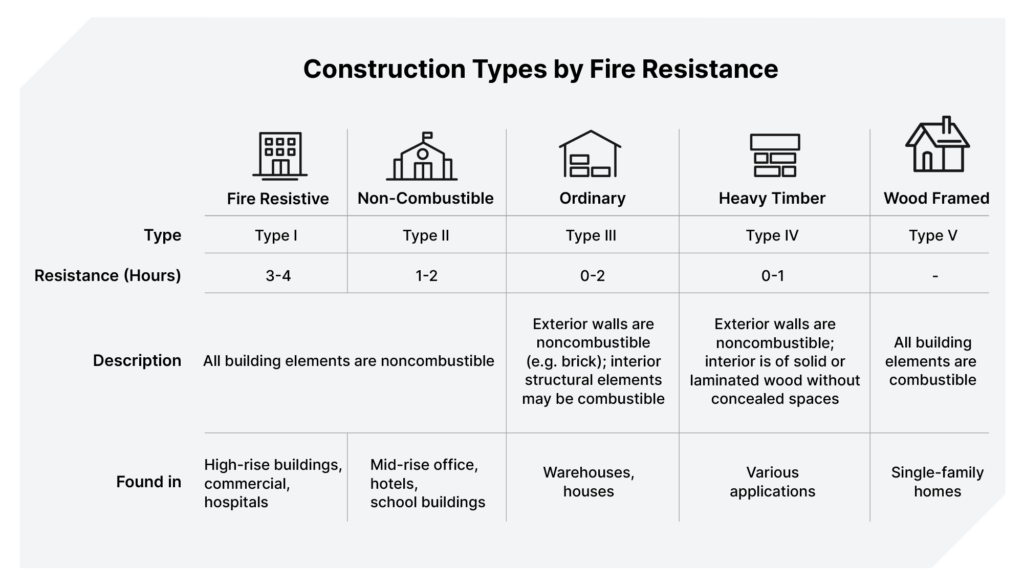

Fire resistance

Codes often classify buildings – and the materials used in their construction – by a fire resistance rating. This is a safety measure used to calculate the structure's ability to withstand a fire.

These standards are found in the Building Construction and Safety Code produced by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). Fire resistance rating can be applied to specific materials or building elements, or to buildings as a whole based on the materials used.

The fire resistance ratings apply to structural building materials, including those used on exterior and interior bearing walls, columns, beams, girders, trusses and arches, as well as floor, ceiling and roof assemblies.

There are 5 main types of buildings according to fire resistance rating:

- Type I: Fire resistive. All building materials are non-combustible, providing three to four hours of resistance to fire. This type of construction is typically found in high-rise buildings, commercial projects and hospitals.

- Type II: Non-Combustible. All building materials are non-combustible, providing 1–2 hours of fire resistance. This construction is used in mid-rise office buildings, hotels and schools.

- Type III: Ordinary. Ordinary construction provides 0–2 hours of resistance to fire. Exterior walls are constructed of non-combustible materials, like brick, while the interior structural elements may be combustible. This is typically found in warehouses and some residential homes.

- Type IV: Heavy Timber. Heavy timber construction requires exterior walls to be non-combustible, providing 2 hours of fire resistance, with the interior made of solid or laminated wood without concealed spaces. This is often used in churches, small commercial buildings and warehouses.

- Type V: Wood Framed. Wood framed buildings have walls, floors and roofs made of wood, providing little to no fire resistance. This type of construction is common in residential homes in the US.

The material fire resistance requirements are generally set during the design phase of a project, to meet the building codes applicable to the location and occupancy type. The architect or engineer will typically prescribe any fire-resistive materials in the specifications provided in the tender package.

Contractors need to follow these specifications closely during preconstruction. Fire resistance requirements can have a significant impact on material costs, as well as material availability. If a contractor substitutes unapproved materials, whether for cost savings or ease of use, they could cause a breach of contract, be forced to correct their work, and even be liable for damages beyond corrective action.

Improving outcomes for any project type

The type of construction project being delivered will affect almost every aspect of the development: permitting & approvals, design specifications, contractor prequalification and selection, building material needs, equipment, etc.

As a construction project grows in complexity, the number of stakeholders – architects, engineers, project managers, contractors, subcontractors, suppliers and regulatory authorities – grows with it. These projects involve numerous interrelated tasks, tight deadlines and significant budgets, which can be challenging to manage without efficient tools.

Project management software creates a single source of truth for planning, execution and monitoring, giving owners and contractors alike real-time visibility into the data they need to manage their resources more efficiently. Advanced tools can also integrate with specialized platforms for tasks such as building information modelling (BIM), cost estimation and risk assessment, providing a comprehensive solution for managing the entire lifecycle of a construction project.

By leveraging project management software, construction teams can ensure that complex projects – of any type – are delivered on time, within budget and with minimal risks and disruptions.

Categories:

Tags:

Written by

Harshil Gupta

24 articles

Harshil Gupta is a Product Marketing Manager at Procore. Backed by a stint in engineering and rich experience in growth and product marketing, he's enthusiastic about the role of technology in elevating and enabling other industries. He lives in Toronto.

View profileJonny Finity

29 articles

Jonny Finity creates and manages educational content at Procore. In past roles, he worked for residential developers in Virginia and a commercial general contractor in Bar Harbor, Maine. Jonny holds a BBA in Financial Economics from James Madison University. After college, he spent two and a half years as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Kenya. He lives in New Orleans.

View profileExplore more helpful resources

Equipped for Success: The Risks and Rewards of Construction Equipment

Even before written language, humans used tools to build. Contractors couldn’t have built the amazing feats seen and used in everyday life without machinery. From handheld tools to multi-storey tower...

The Percentage of Completion Method Explained

Accounting for income and expenses can present a real challenge for contractors, especially on long-term projects. The percentage of completion method is one of the most common methods of accounting...

What Is a General Contractor?

In the construction industry, a general contractor is the person or company responsible for overseeing a construction project. Property owners will typically hire general contractors to ensure a construction job...

MasterFormat: The Definitive Guide to CSI Divisions in Construction

Often referred to as the “Dewey Decimal System” of construction, the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) MasterFormat is the industry standard in North America for organizing construction specifications. This system enables...