Carl Marcus had an idea—one of those ideas that can take root, feed on its own common sense and sweat, and blossom into a big deal. He’d been building quonset huts for the Norling family, who ran a turkey business in Prinsburg, Minnesota. After a lengthy period of knocking out blue-ribbon quonsets for the Norlings, Carl started thinking maybe he could broaden his base a bit. But Carl was a cautious guy. He approached the idea in carefully measured steps, and only after conducting his own thorough market research. Sort of.

“He had a pickup truck and four guys. They all crammed into the cab,” says Ross Marcus with an uncontainable grin. Ross is Carl’s kid. So to speak. “They pulled a trailer behind, and I think in a lot of cases back then they’d stay with the families they built the quonset huts for. They’d stay right in their houses.”

That is, in the manner of headstrong business leaders everywhere, Carl just dove in and started building an institution. Ross Marcus continues with smiling eyes. “He grabbed his own carpenters and started building quonsets all over Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota. That’s how he started.”

I’m sitting with Ross and his own son, Taylor, in a meeting room in the Austin Convention Center. A window in the room looks down on 49,000 square feet of expo hall, busy with the hive-like movement of 21st Century construction innovators briskly doing business around huge, space-age displays crawling with LED. Pretty much the opposite of four guys in the cab of a pickup.

The Basement Office

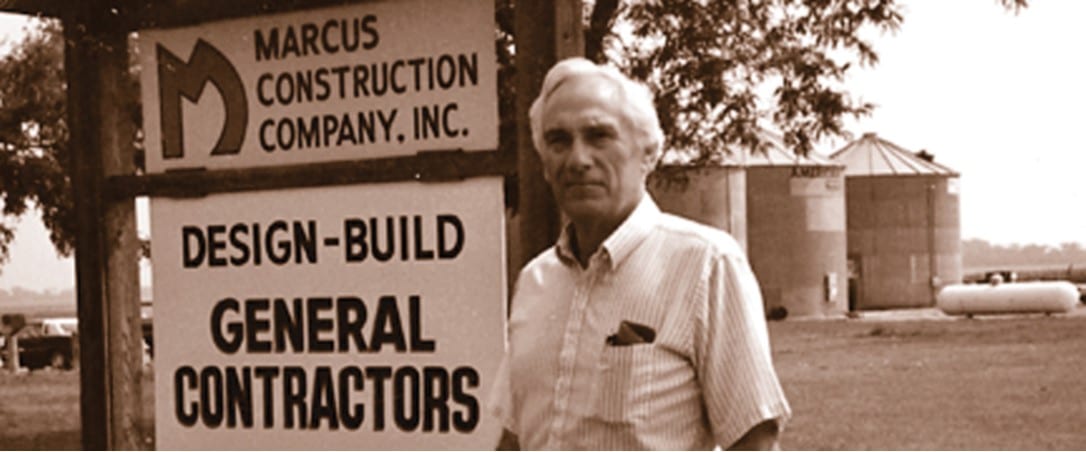

Ross Marcus, President of Marcus Construction, is a tastefully graying guy with the work-softened face and hesitant smile of an aging teenager. I’ve asked he and his son Taylor, the company’s newest hire, to meet with me here at Procore Technologies’ Groundbreak gathering to spell out the history of their family construction business.

“You know, as you look back,” Ross says, “I didn’t think anything different. I worked, you know, from a young guy in junior high or maybe even earlier. There was about 13 acres out around the office and shop, so at 13 or 14 years of age, I was out mowing lawns around there and getting in people’s hair. Then I started working on the crew when I was 15. That’s how I would spend my three months of summer. Dad would put me to work out on a concrete crew pouring concrete.

“My dad started the company in ’56,” Ross says. “He worked out of our small home in Prinsburg, and mom was his secretary and paid the bills. They had an office set up in the basement of their house.”

Which is to say, from the company’s founding in 1956 through to 1962, Marcus Construction was run out of the basement of the family home. It was in ’62 that Carl assembled a proper office in the mobile home he’d dragged onto his own father’s farm. In ’61, Marcus Construction had built their first wastewater treatment plant. How exactly does a builder graduate up to something that complex? Ross starts thinking out loud.

“He was never one to sit and just think, you know,” Ross says. “He bid a couple of those municipal projects, and then I think he just—”

“– and he’s still like that, too, you know?” Taylor interjects with a smile.

In ‘72 Carl, always on the lookout for opportunities to stretch and broaden the company, reached out to Varco-Pruden, a maker of pre-engineered steel building systems. It was a watershed moment in the growth of Marcus Construction.

“It was kind of a monumental step into another business that really is still with us today. We use it in both the commercial side of our business and the agricultural side. So it’s been pretty good.”

In 2017, Ross received the prestigious Varco-Pruden Legends in Steel Award. (“He wouldn’t tell you this, but two years ago…” Taylor had blurted when it seemed Ross was going to move the conversation down the line). The award is bestowed every two years on someone in the business who, by broad consensus, has made a lasting impression in the steel construction community. A video produced to commemorate Ross being so honored captures a crowd of colleagues and Marcus Construction employees extolling Ross’ virtues as a guy who lives by his relationships and does right by people.

So long, Silos

In ’78, Marcus began building flat grain bin storage facilities; a horizontal alternative to the iconic vertical grain silo.

“It accommodates more volume in less square footage for a better price,” Ross explains. Hard to argue with that trifecta. Right around that time, Marcus also began to split its business.

“We have a commercial side of our business, which stays local around Willmar; churches, schools, healthcare, light industrial. So that’s one facet of our building. And then there’s the ag side. It’s just who we are in the Midwest.”

In 2001, Marcus scaled once more, and dramatically.

“We designed and built a big fertilizer storage for Western Consolidated co-op in Holloway, Minnesota.” The fertilizer buildings they’d been constructing to that point were “…3,000 to 4000 tons, 5000 tons. And then the first one we built for Western Consolidated co-op was, I believe, 34,000 tons.”

Apart from the difference in scale, the gentleman from Western Consolidated had asked that some logistical innovations be placed on the menu, too. For instance, a line of 60 to 90 railway cars would obediently line up and wait to be unloaded. According to common practice a rail car would take ½ hour to unload, and that was at full speed. Ross picks it up.

“And he said no, we’ve got to figure out some way to design this so that it’ll unload in 10 minutes. And the handling equipment people at that time, they said they could only design a conveyor across a peak and in the tunnel that’ll handle product at 400 tons an hour. And he said, ‘that’s not fast enough’. He did the math and he said, ‘we need to be able to unload at 800 tons per hour’.” Ross looks at me.

“So we designed it and we built it for him. We did it. And now a lot of that equipment in those big buildings are unloading at 1200 tons an hour. He was one of the trend-setters, for sure.”

As is Marcus Construction, clearly.

You Can Come Home Again

Now that Taylor is signing on, what are Ross’s thoughts? “I never pressured him to come into the business. I said, if you want to do it, you’re welcome to do it, but you’ve got to be happy with what you do in life.” Taylor picks it up.

“I worked in PR and marketing automation, then worked for a private company that got acquired. I worked for Marcus Construction in the summers, but not quite the way my dad did on the crews and stuff. You know, the guys would joke around—oh, here comes the golden boy! It was said in a very endearing sort of way, you know. I liked it…

“But I wanted to earn my own stripes a little bit, so I stayed in the cities for a few years, and I ran marketing automation software. I administered our CRM, and then I moved into more of a marketing communications role.” So, what’s it been like, coming back to Willmar and into the company?

“To me it’s the family business—part of our family, really. But to people in Willmar it’s something else, too. My wife was a teacher and she came into town, and she would say, you know, ‘my husband works for Marcus Construction’. And the reaction would be ‘oh, I know so-and-so that works there’. It’s so cool to see, having removed myself from a situation for a few years and coming back in. You have a fresh perspective of everything, a perspective you didn’t have before. It’s a business to be proud of.”

Lowell and Ben. And Carl.

A company that has its roots in community will rarely be at a loss for talent. “I remember vividly as a young guy,” Ross says. “In 1975, we had a guy in Prinsburg where I grew up; pretty small community, 450 people. There was a guy there that had a little barber shop in town, in Prinsburg. He was going broke. There’s just not enough people to cut hair, you know?” Ross starts grinning. “So my dad went to him one day— his name was Lowell Slagter. He’s passed away now. But my dad went to Lowell and said, ‘Lowell, I think you need to close your barber shop, and I think you need to come to work for me.’” Lowell later became a concrete superintendent, and later a steel superintendent. “The guy was just a hardworking guy,” Ross says.

“And my dad did that with several other guys, too. You know, Ben Dykema was a young man returned from the Vietnam War. He grew up in the little town of Roseland, right next to Prinsburg. My dad put Ben to work, too. And Ben was a beast of a guy. I mean, not very tall but strong as an ox. Everybody liked Ben.” Ross looks distractedly at the tabletop, feeling the memory, then looks me in the eye. “He could get you to do things for him that other guys just couldn’t do. And he’d get you to smile while you were doing it.”

“Ben and I became very close friends. We built a big lumber mill up in northern Minnesota, and Ben went to work up there. He got to know those guys pretty good and decided to make a career change. And he moved up there. I see Ben every once in a while. Maybe once a year I run into him when he comes down. There’s a lot of stories like that with my dad, you know, that he just…” Ross’ voice trails off.

“Dad really always was a proponent of that,” Ross says. “If there’s good people that come along, you’ve got to find a way to hire them.”

Inspirement

Today Marcus Construction is an agricultural construction powerhouse. At this writing Carl Marcus is 91, ”retired”, and as restless as ever; likely one of those guys who regards the passage of time—when he thinks about it at all—as something to swat at in annoyance, like a gnat.

“So he’s got a woodworking room,” Ross says. “It’s kind of built especially for him, a 14 x 30 woodworking room, and he’s got a table saw and miter boxes and lathes and sanders and drills.”

“He’ll put on his work clothes and work for a couple hours,” Taylor says, grinning. “He’ll come into the house and drink some coffee, then go back out.”

“And then he’ll go home,” Ross says. “You know, when he’s there he’ll stay two, three hours and work in his wood shop. Then he’ll head back home. My mom’s still alive at 87. Yeah, I’ve been blessed that way, for sure.”

Marcus Construction remains an idea a guy named Carl had in 1956, in Prinsburg, Minnesota. Some 60 years later, two of the Marcus guys and I are in a meeting room perched high above an acre of polished concrete, a high-tech expo floor seething with construction folks, well-heeled and doing business. Ross describes again his dad and the guys crammed into the pickup, driving between states to build quonsets, staying with the customer till the project was done.

“Two wheel drive,” Ross says with something like wonder. “Busting through the snow in the wintertime. And cold, yeah.”

“Unbelievable,” I say. Ross concurs with a slight smile.

“Yep.”

If you liked this article, here are a few eBooks, webinars, and case studies you may enjoy:

How to Increase Your Construction Profits

Building Empathy – Understanding the diversity of different generations in the workplace

Leave a Reply