— 8 min read

Construction Programming: The Importance of Pre-Design Work

Last Updated Aug 20, 2024

Last Updated Aug 20, 2024

The opening phases of a construction project may be defined differently depending on who you’re talking to. In a general contractor’s mind, for example, the process starts when they get invited to bid. But a lot of work needs to happen before the bid occurs — including developing the drawings and specifications.

In fact, this work often begins well before pen is put to paper to draft even very early drawings. During construction programming, the earliest phase in some projects, architects and design teams do exploratory work to understand what the project requires. How many rooms do we need? What are the space requirements for the building? Are there any specialty spaces, like a clean room, that need to be included? Answers to these questions act as the building blocks for the design.

The level of construction programming varies from project to project. On some jobs, it’s not a large effort and can be completed with a few conversations. On others, this pre-design phase design work takes months. When it’s done well, programming makes the later work of construction management — aligning budget and schedule with the quality the owner expects — much easier.

Table of contents

What happens during construction programming?

The programming design phase is one of the very first things that happens on a project, kicking off the project design phase, which initiates the design work.

Depending on the client, the programming phase is something that can be done well-before a design team signs a contract. There are some companies that focus on programming services only. They will work directly with clients to create a requirements package that outlines all of the building needs, space sizes, adjacencies, etc. This information is then given to the design team who will take the information into the subsequent design phases — schematic design, design development and beyond.

Also called space planning, this phase tasks the design team with understanding the spaces within the building and their relationship to one another. At the same time, that team needs to align those spaces and their functionality with the owner’s expectations. Essentially, this pre-design phase of construction work firms up the earliest details needed to move the project forward.

During programming, the design team explores:

- General project requirements

- The owner’s goals for the build

- Any must-meet delivery deadlines

- Applicable regulatory standards

Take, for example, a university building. During programming, the design team might seek to explore how many classrooms are required in the structure, and how many people need to fit in those classrooms. They might also ask the owner about any space-relationship requirements, like whether the laundry room needs to be adjacent to the dorms. The design team would bring their own knowledge to the table as well. They understand building code-related requirements and any requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

This information gathering usually isn’t performed extemporaneously. Design teams often have tools they leverage during programming, like questionnaires and space-planning matrices.

That said, it’s best practice to capture any details the owners or other stakeholders share even in casual conversation. Programming sets the table for the design phase, so architects and their teams use it to gather as much information as possible to inform their next steps.

From programming, design teams move into schematics.

When does programming happen?

The workflow for programming gets tailored to the project, and it might not happen at all. Bigger clients may have their own internal teams that manage the programming and hand that information over to the architect in the request for proposal (RFP).

Alternatively, the project owner may already know the requirements of the space. For example, the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) has its own facilities standards, called P100. And when the structure will be an iteration of past work (like hospitals or malls), programming is a bit easier because the design team has precedent projects to review and help find answers they need.

Programming is always needed at some level. The design team must receive or create the space requirements for the project through programming. Programming is easier for standard or repeat projects, like hotels. However, the higher the level of customization the project requires, the more extensive the programming phase becomes.

Stakeholders in Programming

Typically, there are two main stakeholder groups in this pre-design phase of construction: the project owner and the design team. The latter might be an architecture firm or a design-build firm, depending on the project delivery method.

The design or design-build firm usually assigns an internal team to the programming work. That team will often be helmed by a lead (e.g., an associate at the firm) who interfaces with the owner. That person then delegates work — like completing a specific programming questionnaire — to others.

Other parties might be brought into construction programming, depending on the project’s requirements. For example, if there’s a bespoke element that the owner wants, the design team may seek out programmatically similar buildings or projects for reference, as well as interview the facility managers, occupants, and other users of the space.

At a design-build firm, the design team will often loop the contractor assigned to the project in as they explore this pre-design phase work. Alternatively, if the owner already knows the contractor they plan to use, communicating with that team can pull in helpful budgetary and scheduling information. While these two topics aren’t must-haves in programming, they are helpful context to have early in the project. For instance, if a specialty type of material is needed for a unique room type — like soundproof glass — this might impact the schedule later on.

Stay updated on what’s happening in construction.

Subscribe to Blueprint, Procore’s free construction newsletter, to get content from industry experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Deliverables From the Programming Phase

By the time programming is complete, the design team should understand the spaces required on the project and how they relate to each other. To capture that information in a way they can use throughout the design phase, they might have some combination of the following:

- A questionnaire (or several) completed by the owner

- An adjacency matrix outlining which spaces need to be near one another, and which need to be separated (e.g., retail space adjacent to the lobby, a restroom separated from a food prep area)

- A room data sheet outlining requirements for specific room types (e.g., “Classroom A,” “Hospital Patient Room B”)

- A program diagram showing which spaces will go where and the approximate scale of the spaces

With all of this in hand, the design team and owners can start to answer the questions of: how long will the project take and how much will it cost?

This first step of information gathering helps the team begin to estimate a cost-per-square-foot for the project. This informs the design as it moves forward. Say the owner has budgeted $20 million for the project but receive an estimate of $40 million based on what they learn during construction programming. At this point, the owner can either decide to expand their budget, phase the project, or instruct the design team to make programming cuts in specific areas.

Similarly, if the project needs to be delivered by a certain deadline, by the end of the programming phase, the design team can advise the owner on any adjustments that need to be made.

Construction Programming in Action

In a joint effort between the GSA and the Department of Defense (DOD), the Foreign Affairs Security Training Center (FASTC) was built to provide specialized training to members of the U.S. Department of State (e.g., embassy personnel and their security teams). An elaborate project with a footprint larger than Manhattan, FASTC includes a fake city, repel towers, a live fire training center, and other highly specific training grounds, along with classrooms and office buildings.

By leveraging the construction programming phase, the design team learned about the DOD’s extensive requirements for the training center. To understand how the design could meet those standards, the team solicited information from a range of parties, from a tactical consultant to the facilities managers operating repel towers elsewhere in the country.

Programming for this project was time and resource-consuming, but it enabled the design team to understand all of the details required to build such a specialized training center, and to best ensure the safety of the people who use it to this day.

Key Benefits Reaped From Programming

People evaluating a project’s timeline — and especially frequent users of the critical path method — might think programming is a non-essential step. But this pre-design phase of construction work is a lot like site preparation. Doing it well sets the project up for success and minimizes the chance of unforeseen challenges.

In fact, when done well, robust construction programming de-risks the entire project:

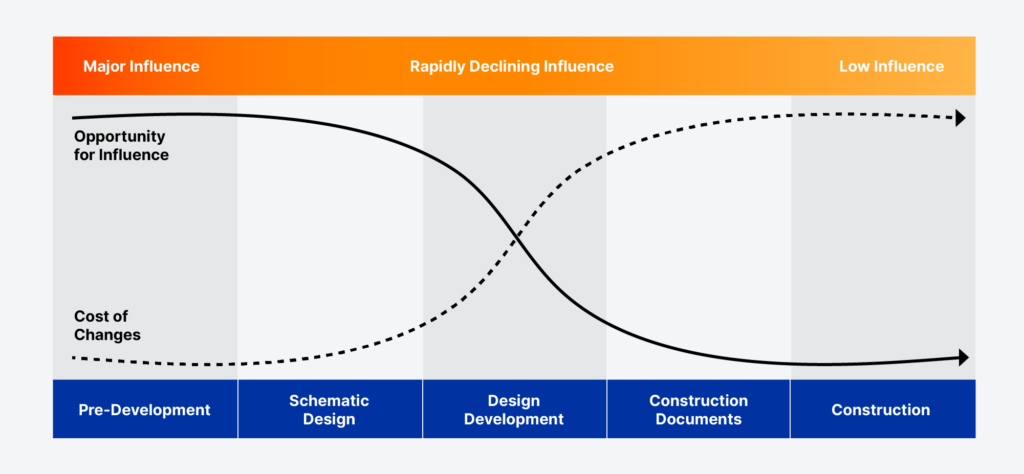

Plus, the most cost-effective time to make changes is during pre-design. If programming surfaces adjustments that need to be made, the earlier you are in the project, the cheaper the adjustment will be. If the project doesn’t include a programming phase, those tweaks might not be discovered until later in the project. If changes come during the construction phase, after the contractor has begun, the price tag increases significantly and comes with a change order.

All told, programming is a helpful tool the owner and design team wield to start the project off on the right trajectory. And when it’s done well, it mitigates risks and prevents cost overruns.

Was this article helpful?

Thank you for your submission.

0%

0%

You voted that this article was . Was this a mistake? If so, change your vote here.

Scroll less, learn more about construction.

Subscribe to The Blueprint, Procore’s construction newsletter, to get content from industry experts delivered straight to your inbox.

By clicking this button, you agree to our Privacy Notice and Terms of Service.

Categories:

Tags:

Written by

Mary Carroll-Coelho

12 articles

Mary Carroll-Coelho is a Product Operations Manager at Procore. A licensed Architect, Mary previously worked for KieranTimberlake, an architecture firm in Philadelphia, in construction and product operations at WeWork, and Director of Customer Success at Willow. She holds a Master of Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania. Outside of work, she volunteers as a mentor in the Spark program.

View profileKacie Goff

55 articles

Kacie Goff is a construction writer who grew up in a construction family — her dad owned a concrete company. Over the last decade, she’s blended that experience with her writing expertise to create content for the Construction Progress Coalition, Newsweek, CNET, and others. She founded and runs her own agency, Jot Content, from her home in Ventura, California.

View profileExplore more helpful resources

How to Understand and Use Architect’s Supplemental Instructions

Architect’s supplemental instructions, also known as ASI, offer a means of making small changes to the construction contract after it’s signed. The ASI is a document issued by the architect...

Improving Project Monitoring with Construction Quantity Tracking

Once a construction project is underway, builders need to closely monitor the project’s progress and make sure it’s staying on schedule and within budget. Quantity tracking helps construction leaders manage...

Streamlining Construction Projects with Effective BIM Coordination

The old saying goes: if you fail to plan, you plan to fail. Construction professionals know this better than nearly anyone. To take a project from a vision in an owner’s...

Construction Invoice Factoring: A Quick Guide

Construction companies need to maintain consistent cash flow. Projects can take years to complete, and delays and unforeseen events may keep expenses mounting. Adding to this load are typically high upfront...